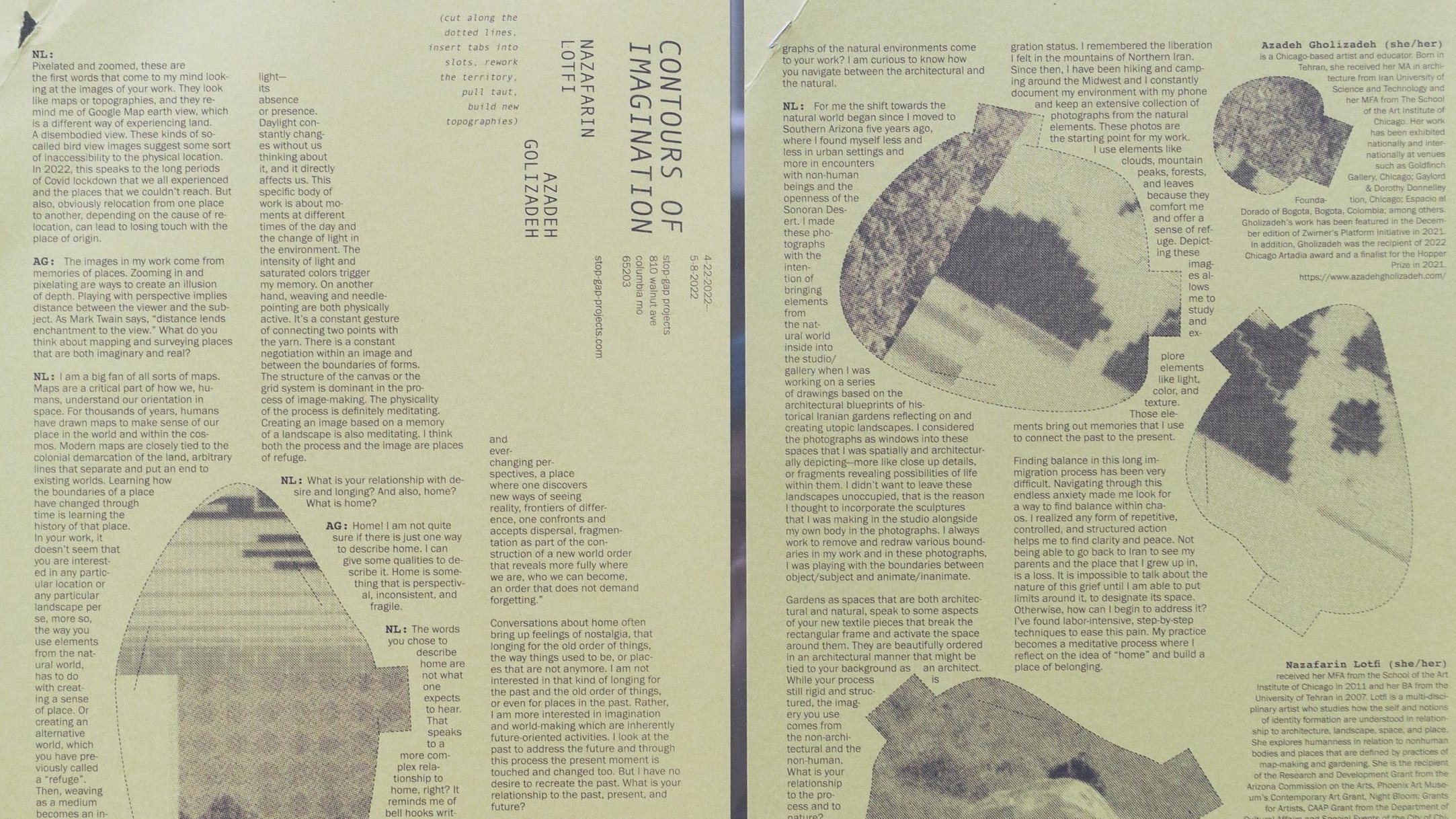

Contours of Imagination

An Interview between

Nazafarin Lotfi & Azadeh Gholizadeh

Nazafarin Lotfi and Azadeh Gholizadeh have been friends for over 10 years, having first met while in graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In conjunction with their joint exhibition at stop-gap projects in April-May of 2022, Nazafarin and Azadeh talked with each other about their recent work, mapping, longing, and the permeable idea of home. Read the interview below and see the riso printed broadside version here

Nazafarin Lotfi: Pixelated and zoomed, these are the first words that come to my mind looking at the images of your work. They look like maps or topographies, and they remind me of Google Map earth view, which is a different way of experiencing land. A disembodied view. These kinds of so-called bird view images suggest some sort of inaccessibility to the physical location. In 2022, this speaks to the long periods of Covid lockdown that we all experienced and the places that we couldn’t reach. But also, obviously relocation from one place to another, depending on the cause of relocation, can lead to losing touch with the place of origin.

Azadeh Gholizadeh: The images in my work come from memories of places. Zooming in and pixelating are ways to create an illusion of depth. Playing with perspective implies distance between the viewer and the subject. As Mark Twain says, “distance lends enchantment to the view.” What do you think about mapping and surveying places that are both imaginary and real?

NL: I am a big fan of all sorts of maps. Maps are a critical part of how we, humans, understand our orientation in space. For thousands of years, humans have drawn maps to make sense of our place in the world and within the cosmos. Modern maps are closely tied to the colonial demarcation of the land, arbitrary lines that separate and put an end to existing worlds. Learning how the boundaries of a place have changed through time is learning the history of that place. In your work, it doesn’t seem that you are interested in any particular location or any particular landscape per se, more so, the way you use elements from the natural world, has to do with creating a sense of place. Or creating an alternative world, which you have previously called a “refuge”. Then, weaving as a medium becomes an interesting choice for this work because weaving is way more physically involved than painting, it is more embodied. Through the process of weaving and needlepointing that you use, you are constantly embedding the figure with the ground, and they keep shifting. There is something very internal in that process. Making spaces within spaces.

AG: I am more interested in the relationship between landscape and memory. Much of my work has been about light—its absence or presence. Daylight constantly changes without us thinking about it, and it directly affects us. This specific body of work is about moments at different times of the day and the change of light in the environment. The intensity of light and saturated colors trigger my memory. On another hand, weaving and needlepointing are both physically active. It's a constant gesture of connecting two points with the yarn. There is a constant negotiation within an image and between the boundaries of forms. The structure of the canvas or the grid system is dominant in the process of image-making. The physicality of the process is definitely meditating. Creating an image based on a memory of a landscape is also meditating. I think both the process and the image are places of refuge.

NL: What is your relationship with desire and longing? And also, home? What is home?

AG: Home! I am not quite sure if there is just one way to describe home. I can give some qualities to describe it. Home is something that is perspectival, inconsistent, and fragile.

NL: The words you chose to describe home are not what one expects to hear. That speaks to a more complex relationship to home, right? It reminds me of bell hooks writing about location, margins, and home in her essay Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness, where she writes: “Indeed the very meaning of "home” changes with the experience of decolonization, of radicalization. At times home is nowhere. At times one knows only extreme estrangement and alienation. Then home is no longer just one place. It is locations. Home is that place that enables and promotes varied and everchanging perspectives, a place where one discovers new ways of seeing reality, frontiers of difference, one confronts and accepts dispersal, fragmentation as part of the construction of a new world order that reveals more fully where we are, who we can become, an order that does not demand forgetting.”

Conversations about home often bring up feelings of nostalgia, that longing for the old order of things, the way things used to be, or places that are not anymore. I am not interested in that kind of longing for the past and the old order of things, or even for places in the past. Rather, I am more interested in imagination and world-making which are inherently future-oriented activities. I look at the past to address the future and through this process the present moment is touched and changed too. But I have no desire to recreate the past. What is your relationship to the past, present, and future?

AG: I am also not interested in that sense of longing. I like to actively explore the nature of longing as “a way of looking.” I am inspired by Simon Schama’s book Landscape and Memory, he writes: “[...] rediscovering what we already have, but which somehow eludes our recognition and appreciation. Instead of being yet another explanation of what we have lost, it is an exploration of what we may yet find.” My approach to making images of places relates to this.

Indeed, the meaning of "home" changes with the experience of the one who defines it. The awareness that home is perspectival is liberating. In this sense I am exploring how a place comes to feel like a place of belonging. We both share an interest in architecture, and I have always loved the way you explored space in your drawings and sculptures. How did these photographs of the natural environments come to your work? I am curious to know how you navigate between the architectural and the natural.

NL: For me the shift towards the natural world began since I moved to Southern Arizona five years ago, where I found myself less and less in urban settings and more in encounters with non-human beings and the openness of the Sonoran Desert. I made these photographs with the intention of bringing elements from the natural world inside into the studio/gallery when I was working on a series of drawings based on the architectural blueprints of historical Iranian gardens reflecting on and creating utopic landscapes. I considered the photographs as windows into these spaces that I was spatially and architecturally depicting—more like close up details, or fragments revealing possibilities of life within them. I didn’t want to leave these landscapes unoccupied, that is the reason I thought to incorporate the sculptures that I was making in the studio alongside my own body in the photographs. I always work to remove and redraw various boundaries in my work and in these photographs, I was playing with the boundaries between object/subject and animate/inanimate.

Gardens as spaces that are both architectural and natural, speak to some aspects of your new textile pieces that break the rectangular frame and activate the space around them. They are beautifully ordered in an architectural manner that might be tied to your background as an architect. While your process is still rigid and structured, the imagery you use comes from the non-architectural and the non-human. What is your relationship to the process and to nature?

AG: I used to hike weekly with my dad when I lived in Iran. Those hikes were a time for reflection and when I experienced, for the first time, feelings of freedom. I started longing for that feeling in the political climate of 2017 after having lived in the U.S. for several years on different visas and an ongoing pending immigration status. I remembered the liberation I felt in the mountains of Northern Iran. Since then, I have been hiking and camping around the Midwest and I constantly document my environment with my phone and keep an extensive collection of photographs from the natural elements. These photos are the starting point for my work. I use elements like clouds, mountain peaks, forests, and leaves because they comfort me and offer a sense of refuge. Depicting these images allows me to study and explore elements like light, color, and texture. Those elements bring out memories that I use to connect the past to the present.

Finding balance in this long immigration process has been very difficult. Navigating through this endless anxiety made me look for a way to find balance within chaos. I realized any form of repetitive, controlled, and structured action helps me to find clarity and peace. Not being able to go back to Iran to see my parents and the place that I grew up in, is a loss. It is impossible to talk about the nature of this grief until I am able to put limits around it, to designate its space. Otherwise, how can I begin to address it? I've found labor-intensive, step-by-step techniques to ease this pain. My practice becomes a meditative process where I reflect on the idea of “home” and build a place of belonging.

-

Nazafarin Lotfi (she/her) received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2011 and her BA from the University of Tehran in 2007. Lotfi is a multi-disciplinary artist who studies how the self and notions of identity formation are understood in relationship to architecture, landscape, space, and place. She explores humanness in relation to nonhuman bodies and places that are defined by practices of map-making and gardening. She is the recipient of the Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, Phoenix Art Museum’s Contemporary Art Grant, Night Bloom: Grants for Artists, CAAP Grant from the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events of the City of Chicago. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues such as Artpace, San Antonio, TX; Regards, Chicago, IL; Phoenix Art Museum, AZ; Elmhurst Museum of Art, Elmhurst, IL; Tucson Museum of Art, AZ; The Suburban, Milwaukee, WI; MOCA-Tucson, AZ; among others. Lotfi attended the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program in Spring 2021. In 2015-16, she was awarded an artist residency from Arts + Public Life and Center for the Study of Race, Politics & Culture at the University of Chicago. She is currently Matakyev Research Fellow at the Center for Imagination in the Borderlands at Arizona State University.

www.nazafarinlotfi.com

IG: @nazafarinlotfi -

Azadeh Gholizadeh is a Chicago-based artist and educator. Born in Tehran, she received her MA in architecture from Iran University of Science and Technology and her MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues such as Goldfinch Gallery, Chicago; Gaylord & Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, Chicago; Espacio el Dorado of Bogota, Bogota, Colombia; among others.

Gholizadeh's work has been featured in the December edition of Zwirner's Platform Initiative in 2021. In addition, Gholizadeh was the recipient of 2022 Chicago Artadia award and a finalist for the Hopper Prize in 2021.

www.azadehgholizadeh.com

IG: @azadehgholizadeh